Case Studies

Case 5

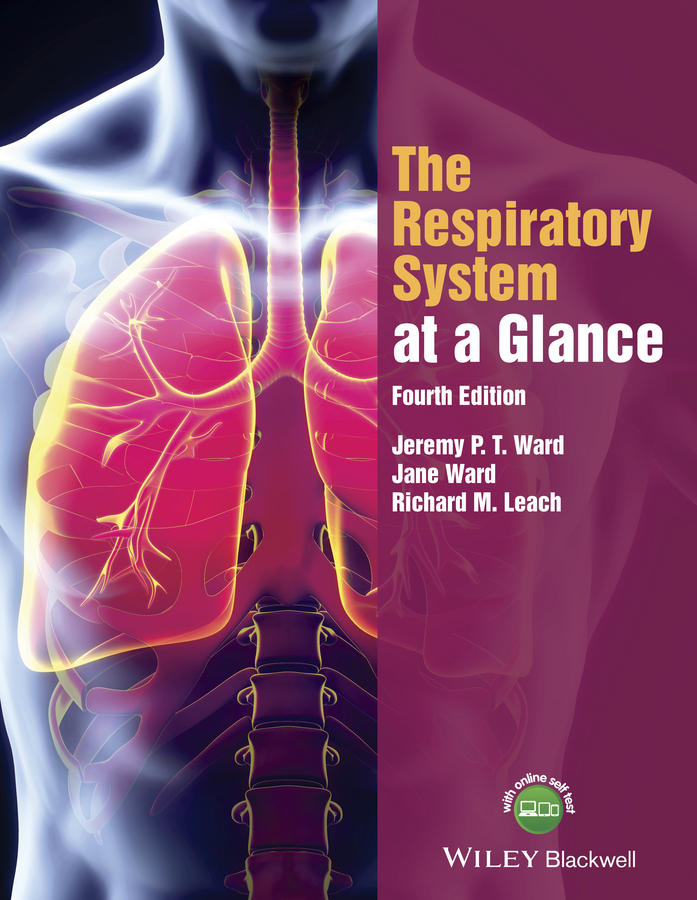

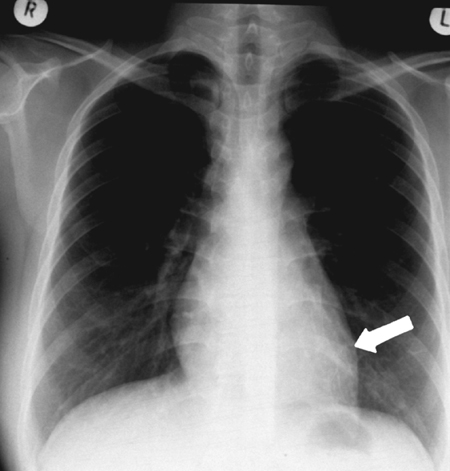

A 31-year-old married Vietnamese woman presented to the Accident and Emergency department following an episode of haemoptysis in which she had expectorated 250 mL fresh red blood. Nasopharyngeal examination by the ENT surgeons was normal, and a chest radiograph (Fig. 47) in the Accident and Emergency department was unhelpful, although bronchial wall thickening was noted behind the heart (arrow). There was no further bleeding, and she was discharged with an outpatient appointment. Over the next few days, she continued to expectorate small clots of blood mixed with discoloured phlegm.

Figure 47 Chest radiograph

At her outpatient appointment, she reported a 10-year history of recurrent, intermittent haemoptysis in which she had expectorated small quantities of fresh red blood, sometimes mixed with bronchial secretions. She had been investigated by several doctors, but chest radiographs were normal, and she had been reassured that the bleeding was from the upper respiratory tract. For the 6 months before her presentation to the Accident and Emergency department, she had coughed up small quantities of blood every 2–3 weeks (<50 mL), but there was no associated fever, wheeze or breathlessness on these occasions. Two weeks before presentation to the Accident and Emergency department, she developed a cough productive of purulent sputum and night-time sweating. As a child, she had suffered with whooping cough, but there was no other past medical history of serious chest illness or tuberculosis. She is a non-smoker.

Examination was normal. She did not have finger clubbing, anaemia, cyanosis or lymphadenopathy. Chest examination was unremarkable. The breath sounds were vesicular, and there were no crackles or wheezes. Routine blood tests, including an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein and sputum microbiology including examination for tuberculosis, were normal. The grade 1 Heaf test was consistent with immunity to tuberculosis.

-

1. What are the most common causes of haemoptysis, and from which circulation does bleeding occur?

Show Answer

Correct answer:

The table below illustrates that most cases of haemoptysis are due to infection (~80%) – including tuberculosis, pneumonia, lung abscess and bronchiectasis. Only a minority are due to malignancy (~20%). Pulmonary embolism and trauma are other potentially important causes. The bronchial (rather than the pulmonary) circulation is the usual source of bleeding.

| Infective (~80%) |

Malignant (~20%) |

Other |

| Tuberculosis |

Lung cancer |

Pulmonary |

| Pneumonia |

Metastatic cancer |

Adenoma |

| Lung abscess |

Lymphoma |

Traumatic |

| Bronchiectasis |

|

Alveolar |

| Aspergillus |

|

Vasculitis |

-

2. Is haemoptysis life-threatening, and how is the severity of bleeding classified?

Show Answer

Correct answer:

Approximately 35–40% of cases of haemoptysis are classified as trivial (flecks of blood in sputum), 45–50% as moderate ( <500 mL or 0.5–2 cups daily) and only 10–20% as massive ( >500 mL or more than 2 cups of blood daily). Mortality is directly related to the rate and volume of blood loss and the underlying pathology. In patients expectorating more than 500 mL of blood within a 4-hour period, the mortality is approximately 70%, compared with 5% in patients expectorating the same quantity over 16 to 48 hours. Death results from asphyxia, caused by flooding of the alveoli and only rarely from circulatory collapse.

-

3. What are the clinical features that may help establish the diagnosis? What is the most likely cause in this case?

Show Answer

Correct answer:

A good history is essential, and may indicate the cause of haemoptysis. The characteristic clinical picture of diseases such as tuberculosis, bronchiectasis and bronchogenic carcinoma may direct subsequent investigation and management. Chest examination may reveal localized crepitations or consolidation, but widespread soiling of the tracheobronchial tree with blood (due to coughing) often results in diffuse clinical signs. Examination of expectorated blood may provide clues. Food particles suggest the possibility of haematemesis, but blood in the nasogastric aspirate does not differentiate between haematemesis and haemoptysis, as coughed-up blood is often swallowed. Purulent material in the sputum may indicate bronchiectasis or a lung abscess. Associated haematuria raises the possibility of an alveolar haemorrhage syndrome. In this case, the age of the patient, the long history of minor haemoptysis and the symptoms of purulent sputum and night-time fever suggest a diagnosis of bronchiectasis, although other potential causes include recurrent pulmonary emboli, vasculitis and a benign adenoma.

-

4. What investigations would you perform to establish the diagnosis in this case?

Show Answer

Correct answer:

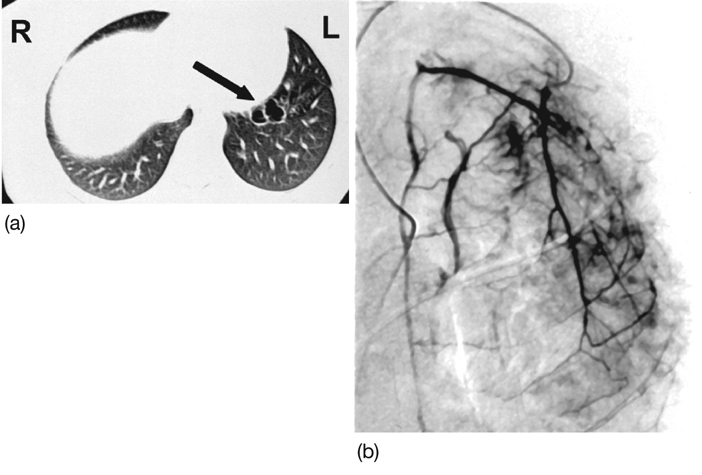

Routine blood tests (white cell count raised in infection), including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (raised in vasculitis) and C-reactive protein (raised in infection). Specialist blood tests (D-dimers for pulmonary emboli, Aspergillus precipitans, vasculitis screen) may be required. Sputum microbiology may isolate infective organisms (pneumonia, abscess, Aspergillus) or acid-fast bacilli (tuberculosis). A screening Heaf test may detect tuberculosis. Chest radiography should be obtained in all patients. It may provide important diagnostic information including evidence of a mass, cavity or abscess. CT scans with contrast may detect the site of bleeding, tumours, vascular malformations and other structural abnormalities. In this case, the CT scan demonstrated a grossly dilated bronchus (>10 mm) consistent with bronchiectasis in the anteromedial segment of the left lower lobe (Fig. 48a). Bronchoscopy is often required to detect endobronchial lesions and inhaled objects (e.g. tooth). Combinations of bronchoscopy and CT scanning have the highest diagnostic yield. Bronchial arteriography may be required to detect the site of bleeding (Fig. 48b).

Figure 48 (a) CT scan and (b) bronchial arteriography.

-

5. What is bronchiectasis, and what causes it?

Show Answer

Correct answer:

Bronchiectasis is described in Chapter 34.

-

6. How should a large haemoptysis be managed?

Show Answer

Correct answer:

The key aspects of management of massive haemoptysis are to maintain a patent airway and oxygenation (oxygen therapy). Asphyxia (not bleeding) is the greatest immediate risk to the patient. Promote drainage of blood and prevent alveolar ‘soiling’ by positioning the patient slightly head down in the lateral decubitus position, with the ‘presumed’ bleeding side down. Determine the cause, site and severity of the bleeding (as above): haematemesis and upper airways bleeding (e.g. nose) may be confused with haemoptysis. Treatment of the underlying cause is essential if the haemoptysis is to be controlled (antibiotics for pneumonia or a lung abscess). Avoid excessive chest manipulation, including physiotherapy, as this may increase or restart bleeding. Cough suppression with codeine 30–60 mg every 6 hours may be helpful. Institute appropriate antibiotics and bronchodilators.

Immediate control of haemoptysis is achieved at bronchoscopy by directing boluses of iced saline with epinephrine (10 mL; 1:10 000 dilution) at the bleeding site.

Bronchial angiography and embolization are the established therapeutic techniques for the initial control of haemoptysis. This procedure is initially successful in 70–100% of cases. The best results are described in patients with dilated bronchial arteries (e.g. bronchiectasis). Re-bleeding often occurs (~40%), and infarction of the anterior spinal artery with paraplegia is reported (~5%). Most studies agree that surgical therapy is associated with the best long-term outcomes for isolated lesions. Primary medical management may be mandatory because bleeding cannot be localized (widespread Aspergillus infection) or is not amenable to surgical resection of a pulmonary segment. In other patients, surgery will be contraindicated because of end-stage lung disease (FEV1 <40% predicted), poor cardiac reserve, unresectable cancer or severe bleeding diathesis.

Final diagnosis: Bronchiectasis of the anteromedial segment of the left lower lobe.